The Bogwood Story

OUR BOGLANDS

Peat is a soil that is made up of the partially decomposed remains of dead plants, which have accumulated on top of each other in waterlogged places for thousands of years.

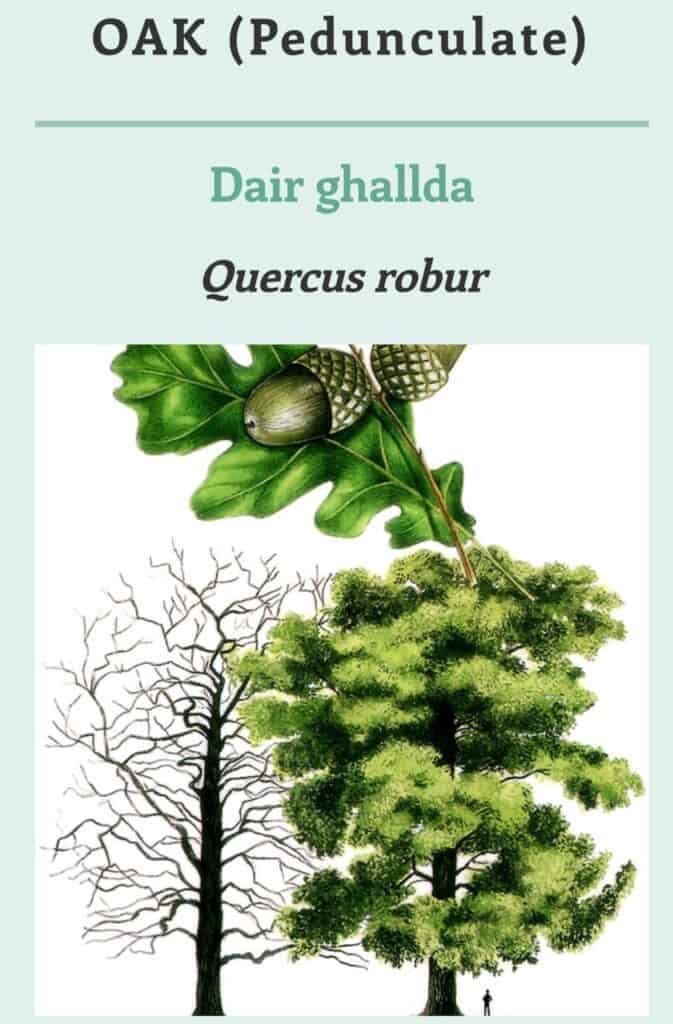

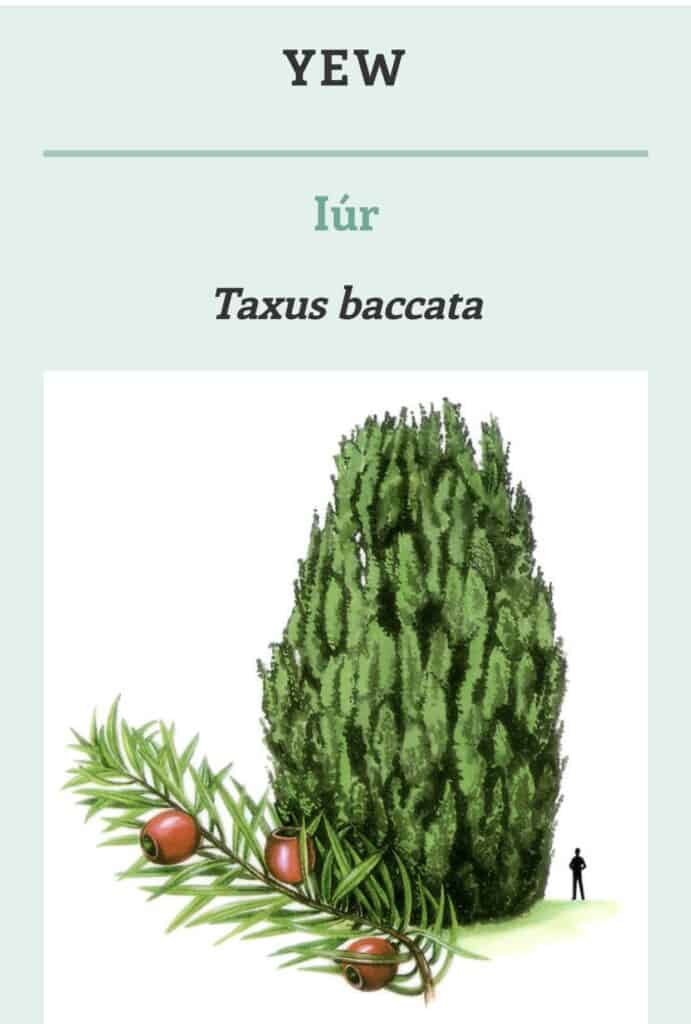

Areas where peat accumulates are called peatlands. Peat is brownish-black in colour and in its natural state is composed of 90% water and 10% solid material. It consists of Sphagnum moss along with the roots, leaves, flowers and seeds of heathers, grasses and sedges. Occasionally the trunks and roots of trees such as scots pine, oak, birch and yew are also present in the peat.

As the summer draws to a close, the boglands stand out most distinctively from the rest of the landscape. The leaves of both the common bog cotton and, in particular, the deer grass (Scirpus caesitosus) turn the sward to a brilliant russet which seems to glow in the low winter light. These russet patches, swathes, or even entire landscapes, are sure indicators of bogland.

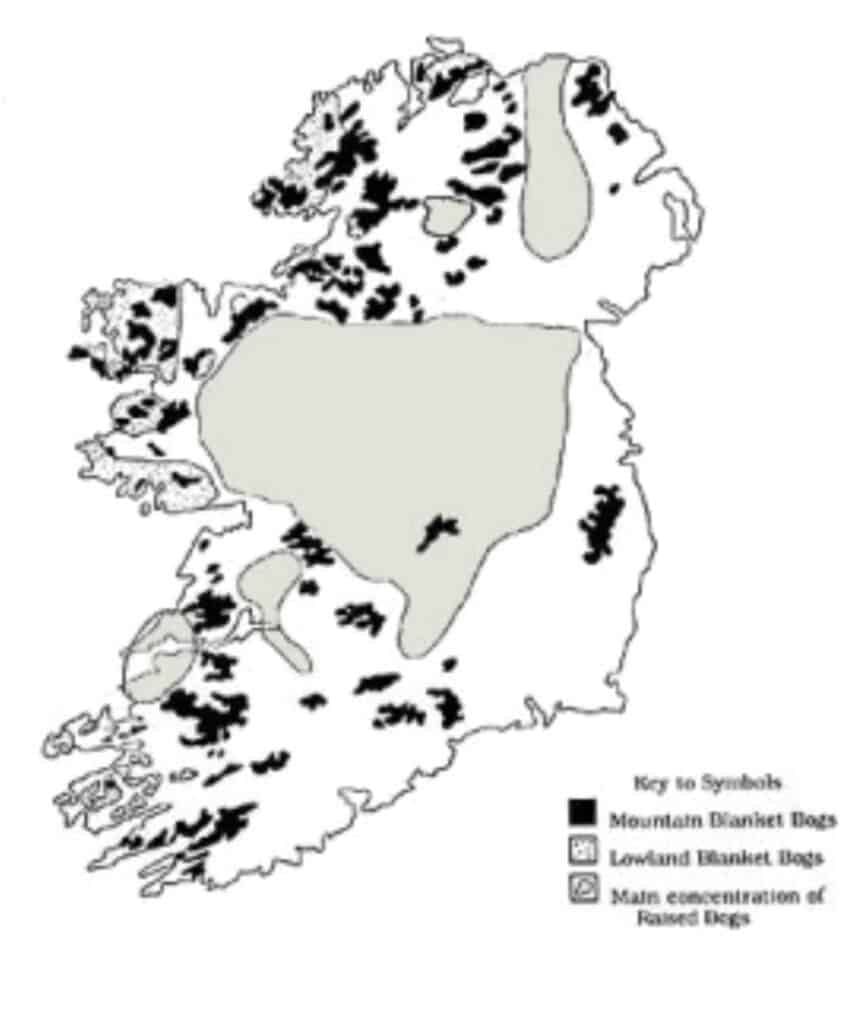

WHERE ARE THE BOGS?

Raised bogs occur in the midlands of Ireland and in the Bann River Valley where rainfall is between 800 and 900mm per year. Blanket bogs are found along the west coast of Ireland and in mountainous areas around the country where rainfall is 1200mm per year or more. 17% of the land surface of this country is covered with peatland and Bord na Móna who are responsible for industrial peatland development in Ireland, owns 25% of the midland raised bogs. Raised bogs once covered almost 1million acres of the Irish landcsape but only 1% of that amount now exist as active living bogs – that is bogs that can support life.

ref www.bordnamonalivinghistory.ie

www.raisedbog.ie

www.ipcc.ie

RAISED BOG HISTORY

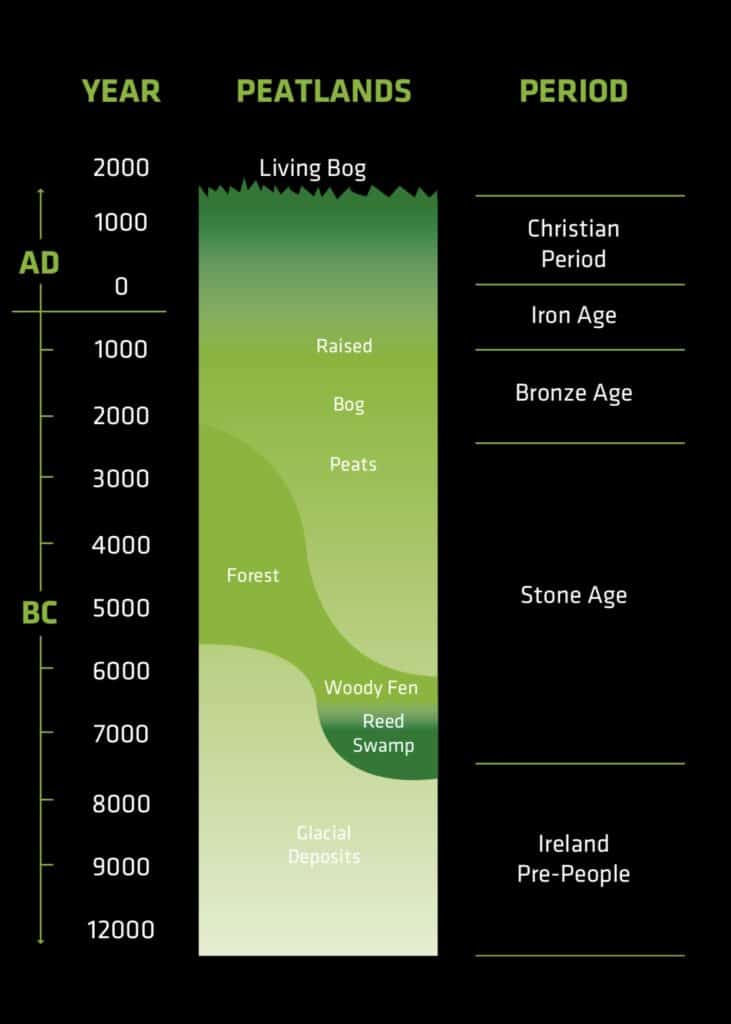

Raised bog formation started at the end if the last glaciation – some 10,000 years ago – when the glaciers had retreated northward. At this time much of central Ireland was covered by shallow lakes left behind by the melting ice.

Lakes also formed where glacial ridges, such as eskers, impeded free drainage and trapped the water. At the base of these shallow lakes there were deposits of lake marl overlying clay and glacial drift. These lakes were fed by mineral rich groundwater and springs and supported floating plant communities, which sometimes produced a thin peat layer just above the lake marl. The lake edges were dominated by tall reed and sedge beds. As these plants died, their remains fell into the water and were only partly decomposed. They collected as peat on the lake bed. With time this process formed a thick layer of reed pear that rose towards the waters surface. As the peat surface approached the upper water level, sedges invaded and their remains added to the accumulating fen peat.

In time the fen peat layer in these shallow lakes became so thick (up to 2m) that the roots of plants growing on the surface were no longer in contact with the calcium rich groundwater. When this happened the only source of minerals for the plants came from rainwater, a very poor source of the essential minerals needed for plant growth. As a result plants invaded that were able to grow in the mineral poor habitats on the surface of the peatland. The best indicator of the changing conditions was the invasion of the bog moss or Sphagnum. The moss became common in such transitional fen/bog habitats, and made the ground even more acid, by its ion exchange activity.

Plants typical of raised bogs, such as Heathers, Sundews and Deer Sedge invaded the tops of the sphagnum hummocks, completing the invasion of bog species.

The bog moss is important as it acts like a sponge or candle wick, drawing up water and keeping the surface of the bog wet and waterlogged, in all but the driest periods. So, even though the bog continued to grow upwards, away from the water table, the bog moss ensured that the water table rose in tandem with the rising peat level. During the long history of bog growth, there has been occasional changes in the overall climate in Ireland. About 4,500 years ago the annual rainfall decreased. This caused bog surfaces to dry, and allowed the invasion and establishment of a pine wood land on the surface of the bog. This woodland persisted for some 500 years, until the climate changed again and became wetter. Rapid bog growth recommenced as the surface became waterlogged, and trees died. Tree stumps and whole tree trunks were buried and preserved in the rapidly accumulating sphagnum peat.

The layers of fen and sphagnum peat and the buried pine stumps are often seen exposed by turf cutters at the margins of raised bogs.

LIFE ON THE BOG LANDS

Perhaps the most spectacular and best-known adaptation to life on the bogs is the carnivorous plant. Several species have developed the ability to trap and eat animals as a means of supplementing their meagre diet. The animals are very small and almost exclusively insects, although the sundews (Drosera species) are able to trap the bigger darter dragonflies, which have wingspans as wide as the human hand.

The sweet scented bog myrtle (myrica gale), typical of western boglands, forms a partnership with bacteria in its roots to obtain extra nitrogen, while the common bog cotton (eriophorum agustiffolium ) uses a snorkel technique, relying on large air filled cells in its roots based to survive in oxygen poor environment beneath the living carpet of sphagnum. A family of tiny brilliantly coloured `jewel’ beetles (Donaica species) use these air spaces as living quarters.

Boglands are home to only a few species of animal, yet can boast the largest animal in Ireland today-the red deer. Red deer can be found wallowing in peat baths to rid themselves of flies and parasites, otters and badgers occasionally venture out into the bogs in search of the eggs and chicks of ground nesting plains.

The songs of skylarks and meadow pipits provides incessant background noise on the boglands. But perhaps the most characteristics sounds of the boglands are, first, the rustle and buzz of dragonfly wings on a still, sunny day as these huge insects patrol the pools and hollows that are dotted across the bogs, and cries of the birds. Most evocative of all, however, is the combination of bird-songs; the cry of the curlew, the shout of the grouse and the sad “wheep” of the golden plover.

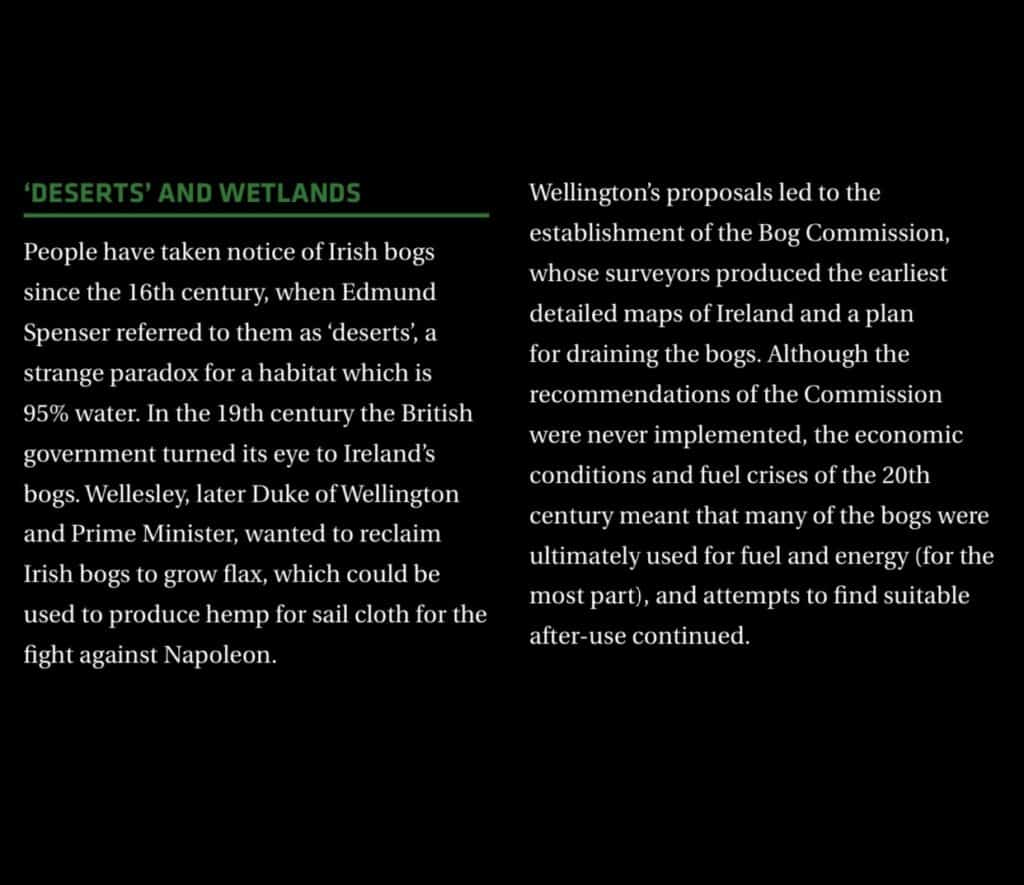

HISTORY OF PEAT USE

Peat has played an important role in the history and development of Ireland particularly in the midland counties. There is documentary evidence that peat has been used as a fuel since the 8th century in this country. The destruction of our woodlands in the 17th century meant the only other fuel available was peat. Prior to the famine the population of this country was 8.2 million people.

It is estimated that at this stage 6-7 million tonnes of peat were used in this country annually. Records show that the earliest attempts at peat use on a large scale was reclamation of the peatlands for agricultural purposes. Several other uses for peat were found in the 19th century varying from peat paper (1835), to peat charcoal (1850), peat moss products (1850), turf distillation (1849) etc. None of these enterprises were successful at that time but showed the commitment the Irish people had in trying to make good use from this freely available natural resource

Moving forward then, to World War II, Ireland found itself in economic isolation, in particular in relation to its energy supply. That led to the establishment of Bord na Móna and the Electricity Supply Board (ESB), in the mid 1940’s, with the role of developing the resources and creating finance in the midlands. This is the context in which the peatlands were developed for industrial purposes.

OUR NATIVE TREES

After the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, Ireland gradually became covered with trees. These spread naturally across a land bridge, which connected Ireland with the UK and possibly the continent. Species, which colonised Ireland naturally, without the influence of people, since the last Ice Age, are referred to as native trees. At first, juniper and birch started to cover the land and this was followed with hazel and Scots pine. Around 8,000 years ago, when conditions were favourable, oak and elm started to expand.

Woodlands of oak, ash, Scots pine, alder and elm developed throughout Ireland between 7,000 and 5,500 years ago and the country was cloaked in a rich tapestry of woodland at that time. The arrival of early farmers heralded the beginning of the steady decline of Ireland’s natural woodland cover. From about 5,500 years ago people have hindered the natural development of woodland by felling trees for timber and clearing the land for agricultural use.

This list of 28 trees and shrubs, drawn from the 8th-century legal tract Bretha Comaithchesa, classifies them in four groups of seven. Due to its date, some of the old Irish names for trees differ from modern versions; translations have been guessed when there was no definite correlation. Different variations exist; in some cases, Blackthorn is listed as a Chieftain.

Airig Fedo – ‘Nobles of the Wood’ (Chieftain Trees):

- Daur – Oak

- Coll – Hazel

- Cuilenn – Holly

- Ibar – Yew

- Uinnius – Ash

- Ochtach – Scots Pine

- Aball – Wild Apple

Aithig Fedo – ‘Commoners of the Wood’ (Peasant Trees):

- Fern – Alder

- Sail – Willow

- Scé – Hawthorn (Whitethorn)

- Cáerthann – Rowan (Mountain Ash)

- Beithe – Birch

- Lem – Elm

- Idath – Wild Cherry

Fodla Fedo – ‘Lower Divisions of the Wood’ (Shrub Trees):

- Draigen – Blackthorn

- Trom – Elder (Bore Tree)

- Féorus – Spindle Tree

- Crithach – Aspen

- Crann Fir – Juniper

- Findcholl – Whitebeam

- Caithne – Arbitus (Strawberry Tree)

Iosa Fedo – ‘Bushes of the Wood’ (Bramble Trees):

- Raith – Bracken

- Rait – Bog Myrtle

- Aiten – Gorse (Furze)

- Dris – Bramble (Blackberry)

- Fróech – Heather

- Gilcach – Broom

- Spín – Wild Rose (Dog Rose)

HISTORICAL USES FOR TIMBER

The first farmers had to create patches of open ground in which to sow crops.

They felled and burnt small areas of woodland, grew crops for several years and abandoned each patch when the soil was exhausted, moving to another piece of woodland and repeating the process. The plough is thought to have arrived in Ireland about 2,600 years ago and this was followed by a substantial decline of woodlands. Uses for timber varied from the construction of bog roads, crannógs and dugout canoes, to ship-building and charcoal for smelting.

Significant areas were also removed to make way, not only for agriculture, but to reduce the cover woodlands provided for ‘rebels’.

A major drive to ‘regreen’ Ireland began after the formation of the State, as people realised just how important it was to have our own supply of timber.

Approximately 9% of Ireland is now covered by forests, mainly non-native coniferous trees. The situation has improved a lot over the last century, nonetheless, Ireland today still stands as one of the least wooded countries in Europe. Trees were very important to the survival and daily lives of people long ago. They provided food, firewood for heat and cooking, wood for spears and fish traps, dye for cloth and poles for fencing and building dwellings.

People valued trees and laid down rules to protect them. Under the ancient Brehon Laws trees were divided into four groups in order of importance and usefulness. Even heather, gorse, bracken and brambles were protected. If you damaged or cut a tree or branch without permission, you would be punished severely.

HISTORICAL BELIEFS SURROUNDING OUR NATIVE TREES

In very early times, trees were associated with religion and the gods. It was believed that Nine Hazels of Wisdom grew at the source of the river Boyne.

Five magical trees were believed to protect Ireland; three ash, an oak and a yew. Sacred trees guarded important tribal sites or wells. Christians adapted these old beliefs and trees were sometimes linked with saints. Old beliefs about trees that survived in folklore. St. Patrick was said to have banished the snakes with an ash stick. Trees beside holy wells were often decorated with rags or other offerings. Rowan was once thought to frighten off witches and bring good luck. The rules to protect trees survived in some beliefs, for example, that cutting down a hawthorn brought bad luck because the fairies used it. The names of trees are seen in place names all around the country.

Derry and Kildare are called after Dair, the word for oak; Glenbeigh in Kerry is named after Beith, the word for birch; Drumkeeran in Leitrim is named after the Caorthann or rowan tree.

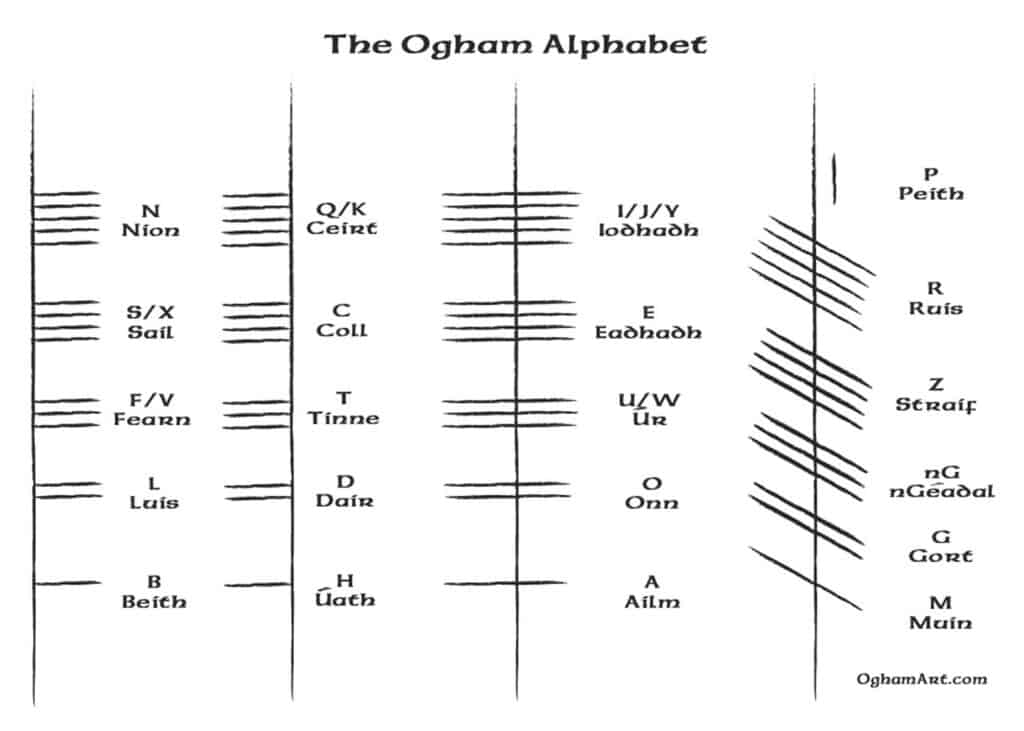

OGHAM WRITING

In ancient times in Ireland, before people used the letters and writing we use today, a form of writing called Ogham was used. We can still see some examples of this on carved standing stones in old monastic sites, in particular Clonmacnoise near the Celtic Roots Studio, in the National Museum of Ireland and in the Ulster Museum. Ogham came from an earlier form of writing, the tree alphabet, where the letters came from the trees the people were familiar with and used. There were only twenty letters in this alphabet.

Fig. 2.1: Ogham Tree Alphabet

HISTORY OF BOGWOOD

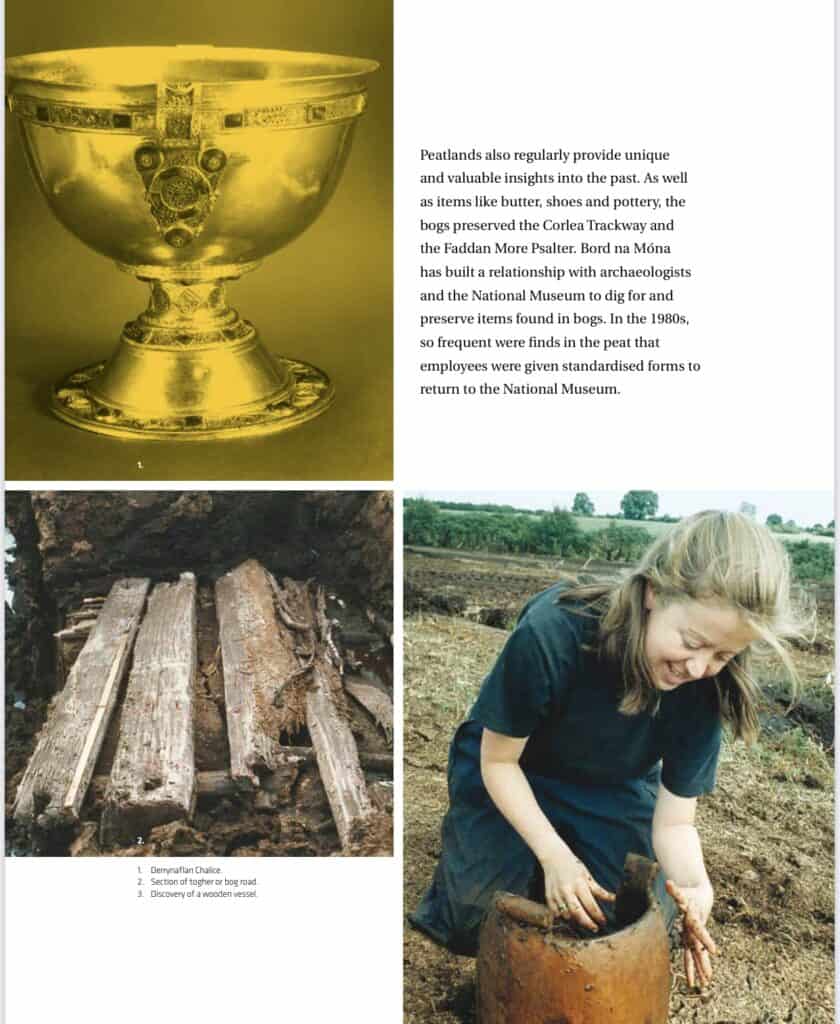

Bogwoods are retrieved from the boglands where they have been buried for over 5,000 years and have come to the surface as a result of turf production.

In famine times in Ireland these woods proved to be an important source of fuel, and were also used for ropes, furniture, torches and thatches. The antiseptic action of the bog causes the texture of the woods to undergo a unique transformation. The oak becomes a fine black, self-lubricating wood, the yew, a rich auburn and the pine takes on a golden hue.

Buried trees and forests are common and widespread in Irish bogs. In extensive areas of the west of Ireland entire forests of pine lie preserved underneath the blanket bog. In raised bogs pine forest is part of the natural vegetation succession from lake to bog. The three important types of wood found preserved in bogs today are Scots pine, oak and yew. They can be from 4,000 to 7,000 years old. Pine, often referred to as deál or fir, is found deep in the bog, and occurred in times when the drying of surface peat allowed a migration of pines on to the bogs. These Scots Pine woodlands were open in character and had an understory of birch. In the ground layer Ericaceous shrubs or heather species were important including Ling heather and Crowberry. They were maintained on the bog for up to 500 years. Eventually the bog surface became unsuited to tree growth and regeneration of the woodland. As the climate became increasingly wetter and bog growth became active again the trees were drowned and seeds could not germinate.

Oak and yew trees are generally found around the edges of the bog and were drowned as the bog expanded out of its basin onto the surrounding mineral soil. The lack of oxygen in waterlogged peat prevents the natural process of decay and ensures the tree trunks and stumps are preserved for years in the accumulating peat.

AGE OF BOGWOOD

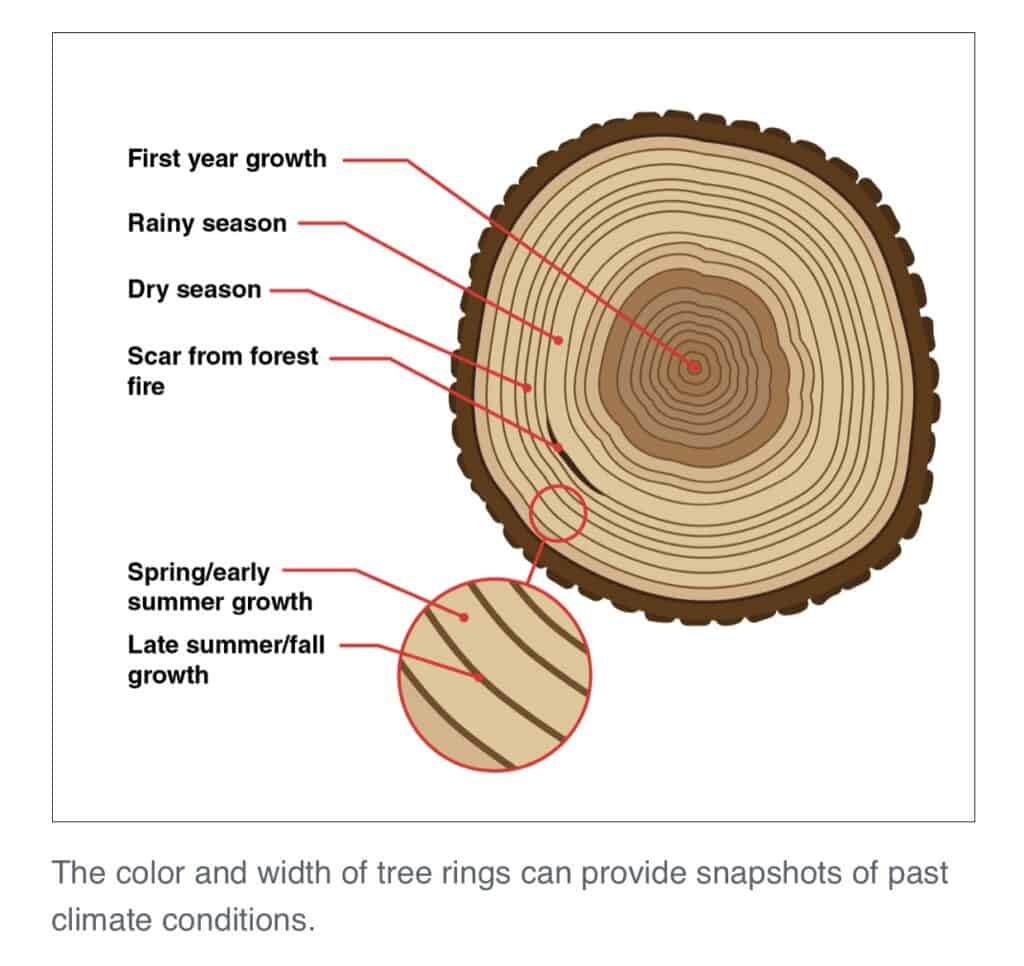

Scientifically, bog wood has proved invaluable as a dating tool and for studying climate change. This is made possible because of annual variations in the diameter size of tree rings. Tree rings are wide in a good growth year and narrow in a poor growth year. Studying variation in the pattern of tree rings is known as dendrochronology. By studying and matching the patterns in tree rings from a wide range of bog wood samples, a year-by-year chronology can be built up. Queens University in Belfast has tree ring records compiled from 4,000 year old bog oak and other ancient oak timbers that span 7,000 years.

A pine chronology for Ireland is also under development. The tree ring chronology allows accurate dating of anything made from oak or pine in Ireland. The annual growth rings in bog wood timbers also give a record of past climatic conditions. The basis of these studies lie in the fact that in a favourable growth year the tree lays down a wide growth ring. In unfavourable years, a narrow ring and so on. The patterns in the rings analysed using statistical packages and related to calendar years give a detailed record of climate change over time.

The Celtic Roots Studio sent samples of their bog oak and bog yew to Queens University Belfast to get the samples of wood carbon dated. The results were as follows:

Radiocarbon dating at Queen’s University, Belfast confirms;

“In providing dates along with sculptured wood, you can safely say, in the case of the bog yew, that the date of the growth of the wood is between 2,000 and 2,200 BC and for the bog oak, the date of growth of the wood is between 3,300 and 3,600 BC.”

Dr. F.G. Mc Cormac, Radiocarbon Research Unit.

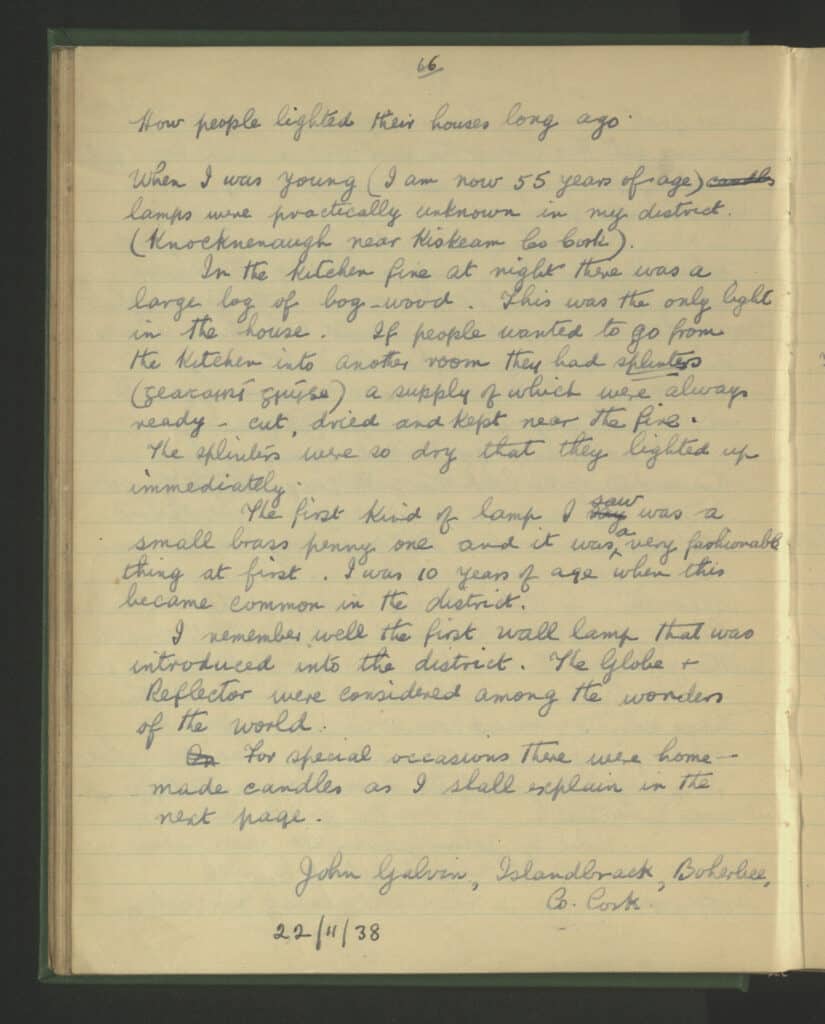

TRADITIONAL USES FOR BOGWOOD

In famine times in Ireland these bogwoods proved to be an important source of fuel, and were also used for ropes, furniture, torches and thatches. For to all that worked the land the relics of the subfossil timber were generally seen as a nuisance, cluttering the bogs and obstructing the business of turf- cutting. We say ‘generally’, and should add ‘in our time’, for these roots and trunks and fallen branches – tough and, one would say, intractable survivors of vast stretches of geological and paleobotanical time – had served generations of Irish people well. Harvested and conditioned by generations of rural expertise (particularly during the famine), bogwoods were once a very important part of their domestic and communal economy. They were in fact an essential resource for the tenant farmer, as for the landless and near landless, when the landlord retained to himself and his household the felling and use of ‘standing timber’. And as the forests were stripped and sold, the bogs provided an answer to the question: “cad a dhéanfaimid feasta gan adhmad?” For bogwoods could, when properly dried and seasoned provide an excellent fuel; and at Christmas, “bloc mór na Nollag”, the Yule log, was commonly of “giúis” or bog fir. The “saor adhmaid” could fashion a roof of timber, or a chair, or a table, or a loom or a boat.

Churns and milk-pails and butter-boards were all made of bogwood. So were ropes for various purposes; on the farm, in the boatyard, even for thatching.

The bogwood torches and candles – “geatairí giúise”, provided domestic lighting, and lights for fishing (legal and otherwise). As to the illumination provided by the bogwood tapers, the journal Béaloideas has record of a Kerryman who read ‘a whole series of Dickens novels’ by their light. The method used to find tree trunks in tact bog remains unexplained today.

People would search bogs for areas wherever the early morning dew, frost or snow disappeared first, these areas suggested the presence of buried wood. A long metal probe was used to confirm the presence of timber. It is said that an experienced hand was able to tell the size, the way in which the timber lay, the tree species and the quality of the timber, all with a metal pole.

BOGWOOD ARTEFACTS

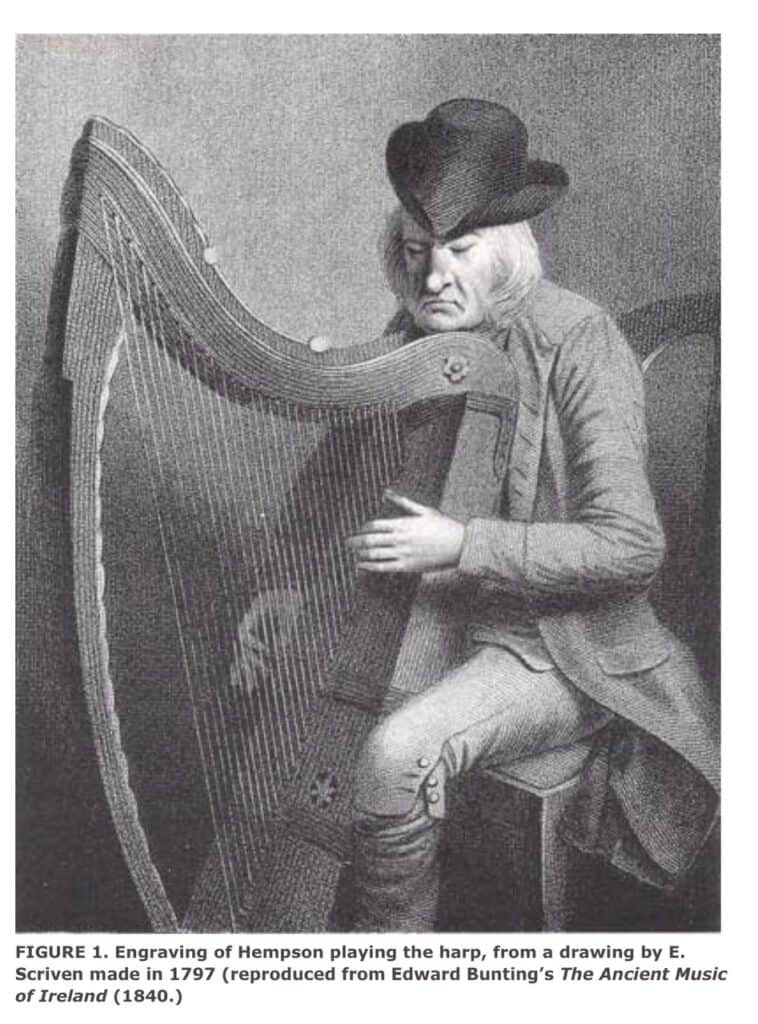

The Downhill Harp Donnchadh Ó Hámsaigh (1695-1807), known in English as Denis O’Hampsey, Hampson or Hempson, was a contemporary of Irish harper Carolan. The ‘Downhill Harp’ was made of bog timber in or near Baile na Scríne in Co. Derry. It was presented to Ó hAmhsaigh (O’Hampsey) on his eighteenth birthday. Harp and harper survived to have an honoured place at the Belfast Festival of 1792. The harp, now a famous instrument with provision for 30 strings, was made by Cormac O’Kelly of Ballynascreene. The bogwood harp was inscribed by him with the following poem:

“In the time of Noah I was green,

Since his flood I had not been seen,

Until seventeen hundred and two

I was found By Cormac O’Kelly underground:

He raised me up to that degree

That Queen of Musick you can call me.”

Hempson played with the Downhill Harp most of his life. When he died in 1807 at the age of 112, his harp was taken to Downhill for safekeeping, by his friend and Patron, Rev. Hervey Bruce. The Guinness family acquired the harp in the 1960’s and it can now be seen in the Guinness Hop Store exhibition centre in Dublin.

Fig. 2.4: The Downhill Harp on exhibition at Guinness Hop Store, Dublin

Bog oak souvenirs, generally speaking, some not particularly attractive articles in themselves, were made for sale over many decades, chiefly in Dublin. Thus Lucas provides us with a reluctant introduction to the second half of his brief account of the past use of bogwoods.

“What might be called the industrialisation of bogwood dates from the early nineteenth century. It flourished in Victorian times, after which it went into a slow decline and was moribund by the Second World War. In its heyday those engaged in the industry produced a vast corpus of work: furniture, statuary’ domestic bric-a-brac and a wide range of items of personal adornment, including brooches, bracelets, and other forms of jewellery. Many of the ‘Irish’ artefacts were either of the wolfhound/Round Tower variety, or else celebrated a drunken Paddy (with shillelagh and pig) but there were also models of castles and abbeys, ‘Tara’ brooches and – one very popular item – the Brian Boru Harp.”

Neville Irons a collector of bog oak work, wrote the following in the Irish Arts Review in 1987, “While there can hardly have been a more intrinsically Irish craft, either in aspect or material, than the beautiful carvings in bog oak and yew of the nineteenth century, yet up to now these have been received little serious assessment. The Art Journal of 1865 did give some account of the origins of the craft. More recently the only published information I have found are six paragraphs in the article “Irish Victorian Jewellery” by Elizabeth McCrum, Assistant Keeper, Ulster Museum, five paragraphs in The Rediscovery of Ireland’s Past, The Celtic Revival, 1830 – 1930 by Jeanne Sheehy, and a three page article by Charlotte Raftery, entitled “Up from the Bog”, published in Cara.”

Research is now removing the layers of surface dust to reveal and industry, the magnitude of which has hitherto been almost totally unsuspected. Not only the carvers themselves, but also retailers and stylistic traditions, have come clearly into focus and the bustling social background against which this Irish minor art flourished has emerged. Patrick McGuirk is generally credited with having been the first professional practitioner of the craft. It is said that he served in the British army, and while at his last posting, Gibraltar, he exercised his carving skill on the local hard coconut shells. He later returned to Ireland and in 1821 presented a carved bog oak walking stick to George IV during that monarch’s visit to Dublin. However, as it was reported that McGuirk presented examples of his carving to the Duchess of Richmond, who was so impressed that she suggested that he use his skill on his native bog oak, one must conclude that his return to Ireland occurred some years earlier while the Duke of Richmond was lord Lieutenant of Ireland, (1807 – 1813).

John Neate (1796 – 1838) is mentioned in The Art Journal, 1865, as having “so far back as 1820 manufactured articles from bogwood and was certainly among the first to profess it, if he did not actually originate the trade”. Neate lived in Killarney, where the baptisms of a daughter and a son are recorded in the Roman Catholic parish register in 1826 and 1831. An elder daughter, Anne, born 1817, married Cornelius Goggin, who may have been trained by John Neate, and who, himself, became a very successful manufacturer of bog oak artefacts.

Although the references to McGuirk and Neate are perhaps the earliest to the professional craft, it no doubt existed at an earlier date throughout the country for the fashioning of small domestic utensils such as spoons and other cooking implements, small furniture, etc. What is certain is that by the time of the 1851 Great Exhibition in Britain, and of the 1853 Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin, it was a firmly and fashionable established feature of the Arts and Crafts scene in Ireland. The 1851 Exhibition catalogue lists several Irish manufacturers and there must surely have been others throughout the country working on a more humble scale in what started essentially as a cottage industry.

Fig. 2.5: Artefacts made from bogwood

OUR CRAFT

During peat production, the ancient remains of trees – over 5,000 years old, come to the surface of the bog. Celtic Roots then retrieves the wood and takes it back to their workshop where it is slowly dried over a period of two years, taking great care not to try to rush the process. Occasionally at this phase it can be anticipated as to what the wood will be best suited for creating. While the wood is drying, each piece is labelled in order to identify it by origin i.e. bog location and species etc.

Depending on the scale of work, the design or the form of the piece, the artist commences working on the wood. Other times the shapes of the sculpture is revealed in the forms inherent in the piece itself. Each piece, great or small undergoes nine different hand processes before it is perfected with a light coating of beeswax. The fine sanding which is synonymous with Celtic Roots’ work, highlights the grain in the wood beautifully.

The pieces created by Celtic Roots, bring together past and present Ireland.

Elegance in its most pure and honest form is at the very heart of all the pieces made. The creative designs use the lines and elegant shapes of the Irish landscape as well as the fluid lines of the flowing water and the soft and natural colours of the landscape’s rich palette. The inspiration for Celtic Root’s designs is the natural hinterlands of the midlands.

The craftsmanship is a celebration of our rich Irish heritage and unspoiled local environment.

THE CARVING PROCESS

We take the old trees into our workshop and dry them very slowly over two years to convert them into wood that can be carved and polished into a sculpture or a jewel to wear.

When it is finally ready to commence the slow work of carving, to reveal the colours and shapes inherent in the wood. Each piece goes through 19 different processes by hand before it is finally bees waxed to highlight the grain in the ancient bogwood.

I feel lucky to be able to work with and feel apart of a long tradition in this material. They are aware of using every remnant of the bogwood and treating it like a beautiful Irish living jewel that it really is.

I work in a sustainable way using basic tools and natural materials, like beeswax and natural oils to highlight the grain in the finely sanded wood. I use recycled paper for the last twenty years in our packaging.

It is these long relationships with the bog, Bord Na Móna and the locality that reinforces our sustainability.